The Research Studio: A Visionary Retreat for Modern Art

The Research Studio, now the Maitland Art Center, was born from a moment of shared inspiration between two unlikely collaborators: Jules André Smith, a reclusive artist and architect known for his satirical wit, and Mary Curtis Bok, a prominent philanthropist and arts patron. The two met in 1936 at the funeral of their mutual friend, actress Annie Russell, and quickly developed a profound friendship. Their letters, filled with humor and shared frustration over the lack of experimental art spaces in Central Florida, became the seeds of a radical new idea.

That fall, Smith wrote to Bok lamenting the missed opportunity for modern art in the region. In response, Bok offered to fund a small gallery of his own design, a space to operate entirely independent from institutional oversight. What began as a simple proposition evolved into something far more ambitious: a walled, architectural sanctuary where artists could live, work, and challenge the conventions of their medium. Within months, plans were underway for what Smith described as an “art laboratory.”

In early 1937, construction began on the Maitland campus. Influenced by Mesoamerican art, theatrical set design, and his own Episcopalian faith, Smith adorned every surface with hand-carved concrete reliefs, incorporating imagery from Christian, Buddhist, and ancient mythological traditions. The layout featured interconnected apartments, studios, courtyards, and gardens, all surrounded by a six-foot wall to preserve privacy and creative focus. Smith called the space Espero, meaning “I hope,” and imagined it as a haven for the spirit of invention.

The Research Studio officially opened its first season on New Year’s Eve 1937. Artists and residents gathered in the courtyard to ring a ceremonial bell, ushering in what would become two decades of dynamic creative activity. Over 65 artists, known as Bok Fellows, lived and worked at the Studio during Smith’s lifetime. They were encouraged to abandon safe practices and embrace experimentation. As Smith wrote in a 1939 article, “The searching in inventiveness is an American trait. What has become of our ‘battle cry of freedom’?”

Despite his generosity, Smith could be demanding. He critiqued artists who failed to step outside their habits, and early seasons sometimes ended in tension. He later moved to a competitive application process, believing invited artists often arrived with inflated egos. Still, many found the Studio to be a transformative and idyllic space. Artist Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones recalled “delicious food, crab croquettes, and alligator pears under the blooming orange trees in the courts.” Privacy was protected, with awnings artists could lower when they wished not to be disturbed.

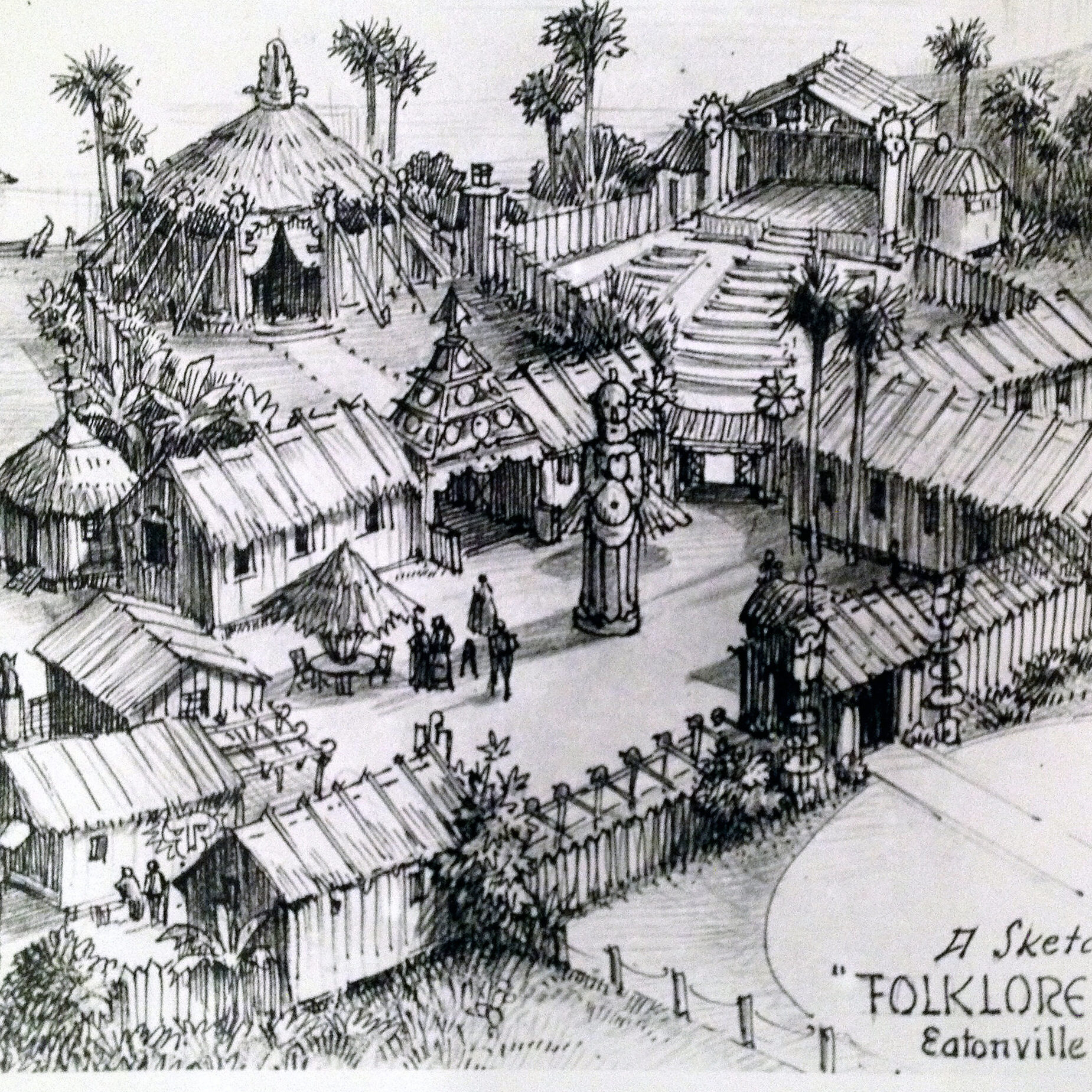

The Research Studio also became a rare space of inclusion during the Jim Crow era. Smith welcomed Black children from neighboring Eatonville for art classes and provided shelter to locals who were caught outside during segregationist curfews. He maintained a lifelong friendship with author Zora Neale Hurston, who shared his interest in preserving cultural heritage. The two even dreamed of a “Folklore Village” in Eatonville, designed by Smith, that sadly never came to fruition.

In the 1940s, the campus expanded again with the construction of the Garden Chapel and Mayan Courtyard, spaces that fused Smith’s spiritual, theatrical, and architectural vision. Relief panels depicting saints, warriors, and surreal motifs line the walls, echoing the fantastical scenes from Smith’s earlier paintings. The chapel became a beloved site for meditation and, later, weddings. Smith would often visit it before breakfast with his prayer book in hand, calling it the “Chapel of St. Francis.”

World War II temporarily paused the residency program, but the Studio remained active. Smith continued exhibiting work in the Laboratory Gallery, often to small but loyal audiences. In the postwar years, he transitioned the studios into self-sustaining apartments, charging modest rent. While he missed the influence he once had on younger, more experimental artists, the Studio continued to host figures such as Milton and Sally Avery, who brought national attention to the site.

Smith lived reclusively in a studio-library compound on the edge of the garden, with longtime companions Duke and Florence Banca managing daily operations. He continued to carve, paint, and write, and his art increasingly reflected the anxieties of the atomic age. “The Bells of Destiny,” he wrote, “are now playing jazz.”

By the time of his death in 1959, the Research Studio had become a fully realized expression of Smith’s singular vision. It was a retreat, a gallery, a school, a stage, and above all, a belief in the power of unfettered creativity. Today, the site stands as a National Historic Landmark, a testament to Smith’s legacy, and to the enduring need for spaces where artists are encouraged not only to create, but to dream beyond the boundaries.