The Paintings & Drawings of J. André Smith

André Smith explored a wide range of styles and techniques throughout his artistic career. Never content to settle into a single mode of expression, he consistently challenged himself to try new trends, experiment with unfamiliar media, and tackle complex themes.

To introduce the breadth of his visual work, we’ve grouped his paintings and drawings into three key categories: European Works, Eatonville Works, and Surrealist Works.

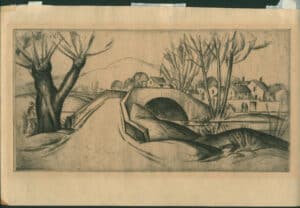

European Works

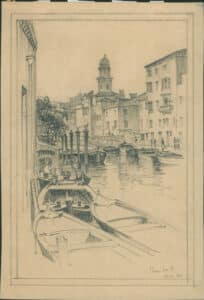

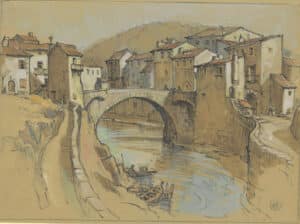

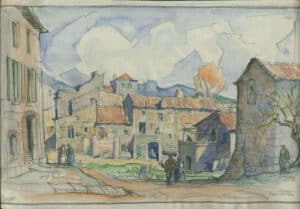

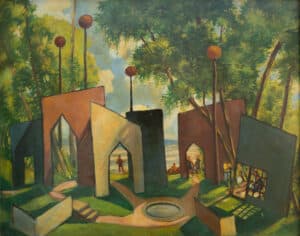

Smith’s early artistic development was profoundly shaped by his travels across Europe. Beginning in 1911, he spent several extended periods abroad, often accompanied by fellow etcher Ernest David Roth. Together, they explored France, Italy, and Spain: regions whose historic towns and landscapes became frequent subjects in Smith’s etchings and watercolors. These early works were marked by a strong sense of draftsmanship and architectural detail, reflecting both his training as an architect and his interest in preserving a sense of place.

Over time, however, these scenes evolved. As Smith matured artistically, he began moving beyond strict realism, embracing expressionistic touches and more experimental compositions. His European works reveal this transformation, shifting from atmospheric renderings of cityscapes to increasingly stylized and abstract interpretations of form and space. This period laid the foundation for the modernist sensibilities that would later define his work at the Research Studio.

Though he returned to Europe regularly throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, Smith’s travels gradually declined as his health worsened. Still, the influence of European architecture and artistic innovation remained central to his practice and served as a bridge between his early career and his later experiments in Florida.

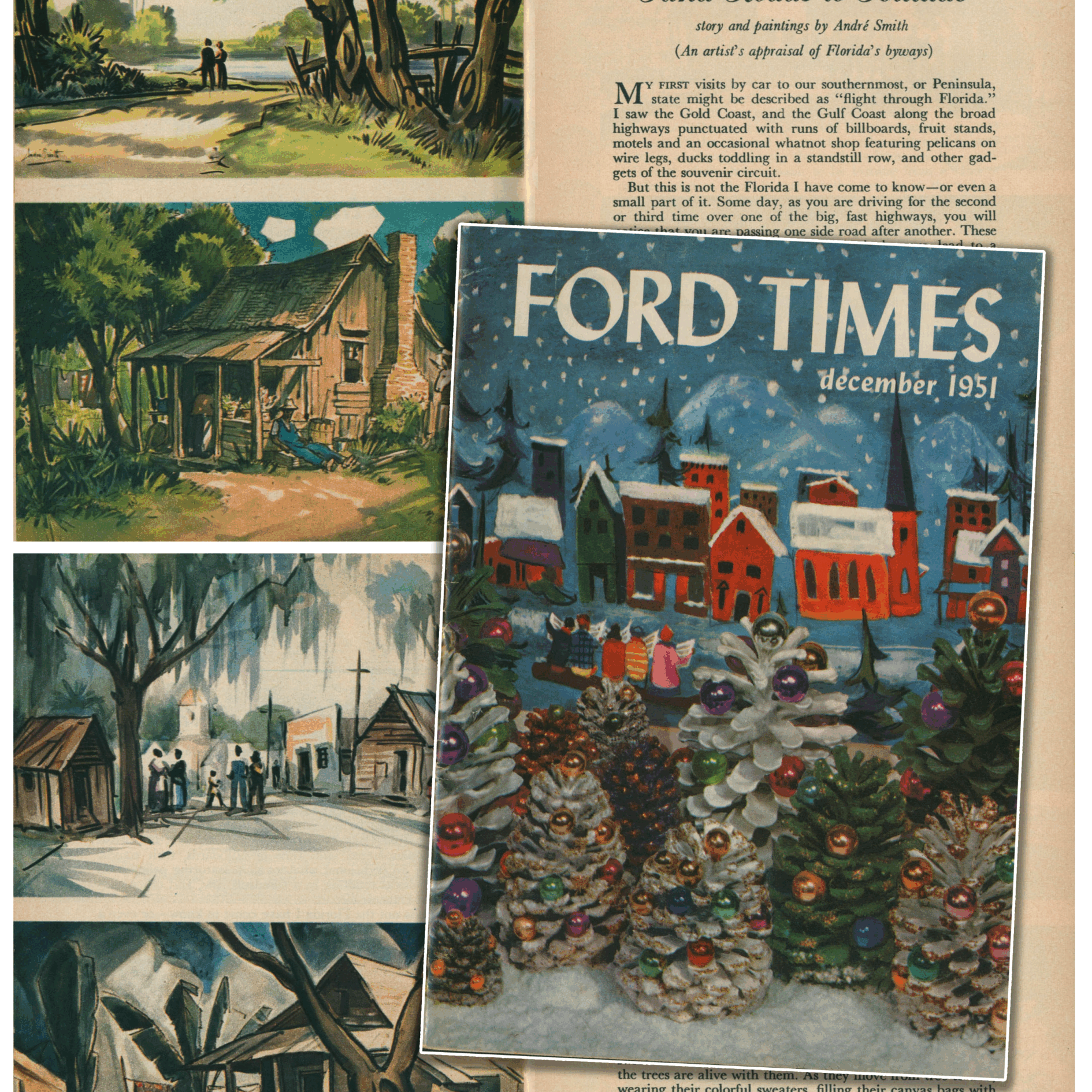

“On byways you watch the orange pickers at work... they present a picture to warm an artist’s heart... these roads lead to the Florida I know. Sit down and choose one.” J. André Smith, “Sand Roads to Solitude,” Ford Times, 1951

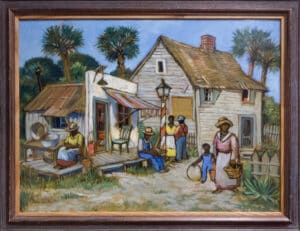

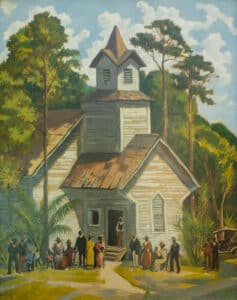

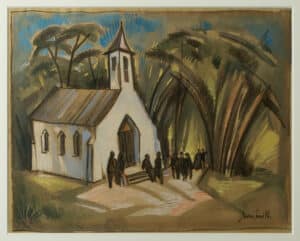

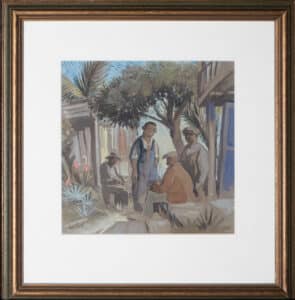

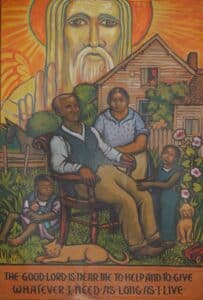

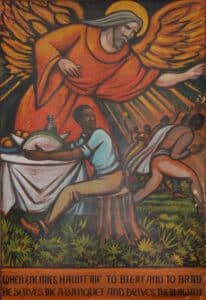

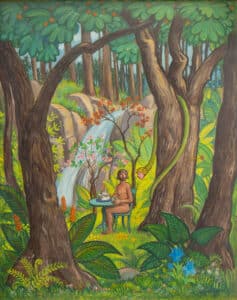

Smith was deeply moved by the people and vibrancy of nearby Eatonville, one of the oldest Black-incorporated municipalities in the U.S. He often sat by the roadside sketching residents at work and rest. In 1936, he began a series of large spiritual panels for New Hope Church in Winter Park, including a now-lost altarpiece depicting a dark-skinned Man of Sorrows. Eight surviving panels based on Psalm 23 were eventually gifted to St. Lawrence Church in Eatonville, where they remain today.

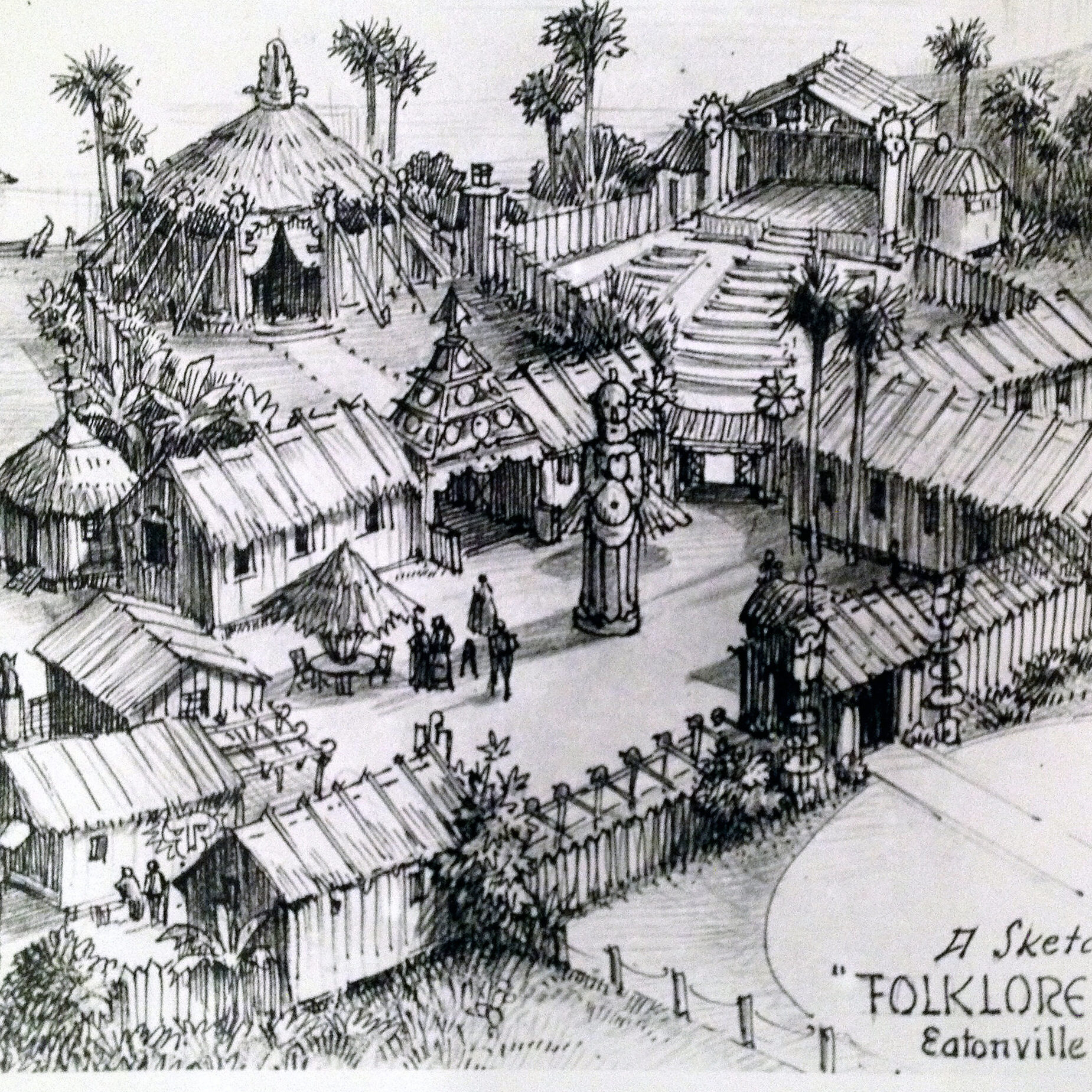

Smith’s work in Eatonville led to a friendship with author Zora Neale Hurston. Both artists found inspiration in the daily life of the community, and their shared interests in art, literature, and cultural identity fostered a creative partnership. At Hurston’s request, Smith even drafted plans for a proposed cultural center called “Folklore Village,” featuring studio spaces, courtyards, and an amphitheater. Though the project was never built, the friendship endured, and the legacy they left behind continues to impact the cultural fabric of Central Florida.

Smith’s Eatonville works blend realism with spiritual and emotional resonance, capturing not just the physical world, but the rhythms of a living community.

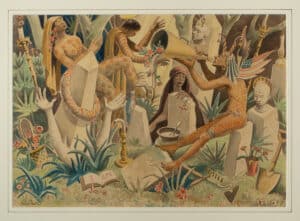

In 1936, Smith embarked on a powerful new chapter in his creative practice, producing a series of watercolor “automatic” drawings. Inspired by the subconscious, these works came to life with little premeditation. He described the experience as: “...being in the position of a rather amazed bystander who sees before his eyes happenings that seem to be only vaguely connected with his own volition.”

Within six weeks, Smith completed 38 paintings. That December, four were included in Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, a groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that also featured works by Picasso, Dalí, Magritte, and O’Keeffe.

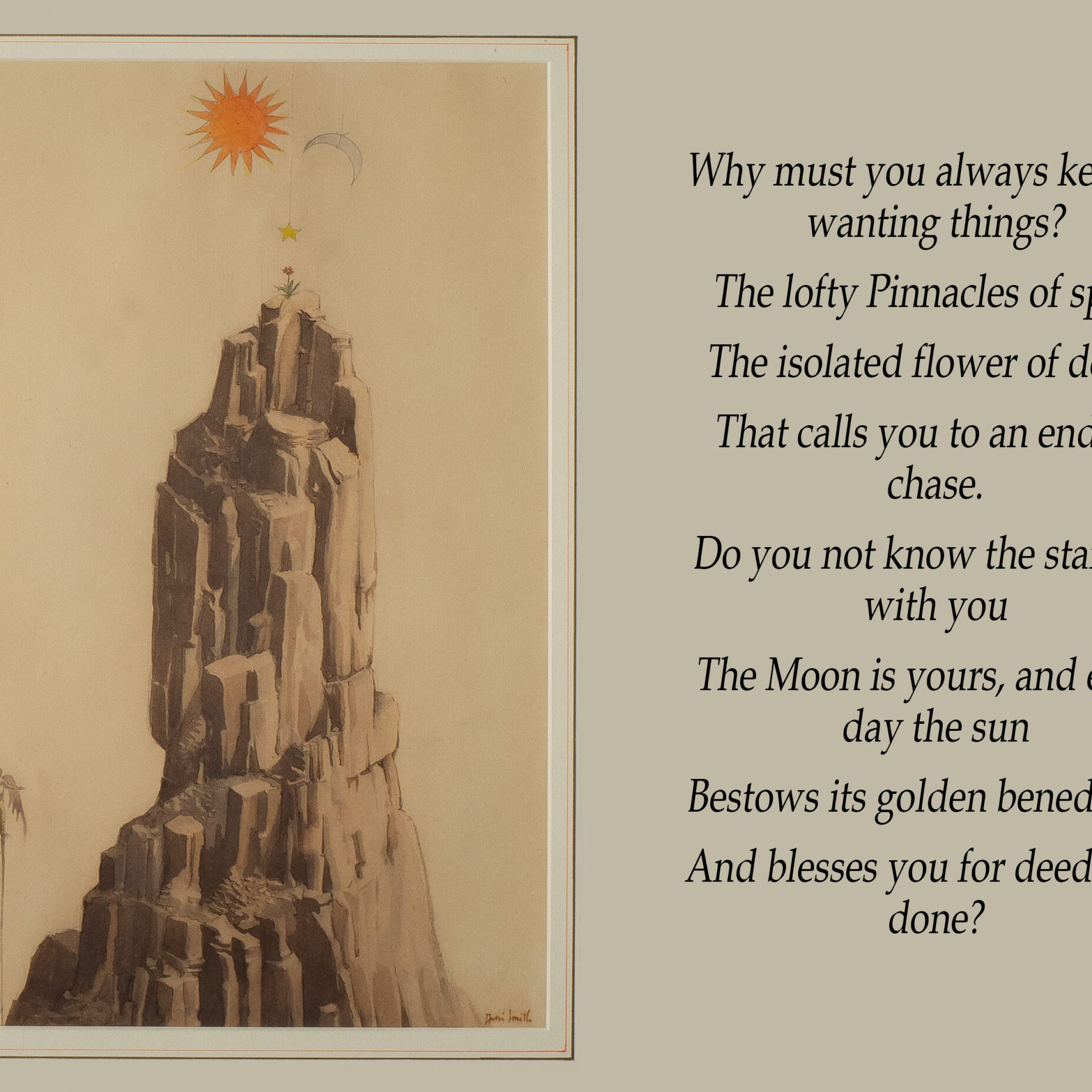

In 1937, Smith published Art and the Subconscious, compiling these surrealist watercolors alongside his essays and poems. In the foreword, he observed: “We are... at the beginning of a new phase of art... a rushing waterfall of new and stimulating creativeness.” Smith later added short poems to each volume, alternately satirical, meditative, and spiritual, which expanded on the ideas and moods present in his paintings.

In a 1939 Art Instruction article, Smith urged American artists to innovate, rather than imitate Europe:

“The searching in inventiveness is an American trait... In music and architecture, we have reflected our true American spirit. In art, we have merely lagged behind.”

Smith saw automatism and surrealism not just as artistic experiments, but as part of a larger cultural shift. By embracing the unknown and elevating intuition over formula, he contributed to a new artistic vocabulary, one that the Research Studio would go on to foster for generations.